Transforming Intention into Practice: Global Partnerships’ Learnings in Poverty Measurement >

An interview with Tara Murphy Forde, Senior Vice President, Research & Impact, Global Partnerships

Global Partnerships (GP) is an impact-first investor dedicated to expanding opportunity for people living in poverty. At GP, we create and manage funds that make loans and early stage investments in social enterprises that serve people living in poverty throughout Latin America, the Caribbean, and sub-Saharan Africa. Five years ago, we spun out our Research and Impact Team to strategically define, measure, and strengthen the impact of our investments. As part of this effort, we developed a poverty measurement methodology that helps us understand whether our investments are reaching those we aim to serve.

Today we use poverty data to screen, select, and monitor the outreach of our social enterprise partners and our analysis informs our investment decisions; not only whether to invest, but on what terms. We continue to iterate and strengthen our approach, but there have been some key steps and learnings along the way, which I will attempt to distill here in the event they are of service to others embarking on a similar pursuit.

As a starting point, it was easy to jump to the question of how we would measure poverty, but it quickly became clear that first we needed to ask why we aim to measure poverty and then make decisions about what we would measure. From there, we were able to develop a poverty measurement methodology that was aligned with our mission and worked with our investment process.

Why Measure Poverty? Asking this question drove strategic clarity regarding our commitment to not only reduce poverty, but to promote deeper inclusion. It crystalized the fact that we invest at the edge of the market, emphasizing approaches that include people marginalized by depth of poverty, but also by other aspects of identity such as gender and/or geography. Asking the question “why measure poverty” clarified that we do so because it is core to our mission, because certain aspects of poverty can be measured, and because it provides us with a critical entry point into understanding the intersectional nature of exclusion.

What Will We Measure? Having clarified why we aim to measure poverty, we then needed to decide what we would measure. To do so, we got up to speed on the various poverty measurement methods and measures and assessed their utility given our aims. In this exercise, we looked at our partners’ practices as well as those of global poverty experts. In addition to philosophical alignment, we considered credibility, comparability, ease-of-use and coverage across our investment geographies. We landed on measuring monetary poverty using the World Bank’s international poverty lines (IPLs) because of their widespread usage, their credibility, and their comparability across our portfolio.

The next step was to integrate the IPLs into the definition of who we aim to serve in each of our Investment Initiatives. To do so, we consulted sector-specific literature as well as regional and partner data and selected an appropriate poverty line (either the $3.20 or $5.50/person/day 2011 PPP line).1 In most initiatives, the poverty line accompanies other aspects of marginalization, such as gender or geography. For example, in our Women Centered Finance with Health initiative we aim to serve female microentrepreneurs living under $5.50/person/day 2011 PPP. By defining this target, we do not expect our partners to exclusively serve this market, but we want to make sure our partners are serving a sufficient number of the clients that the program is designed to reach.

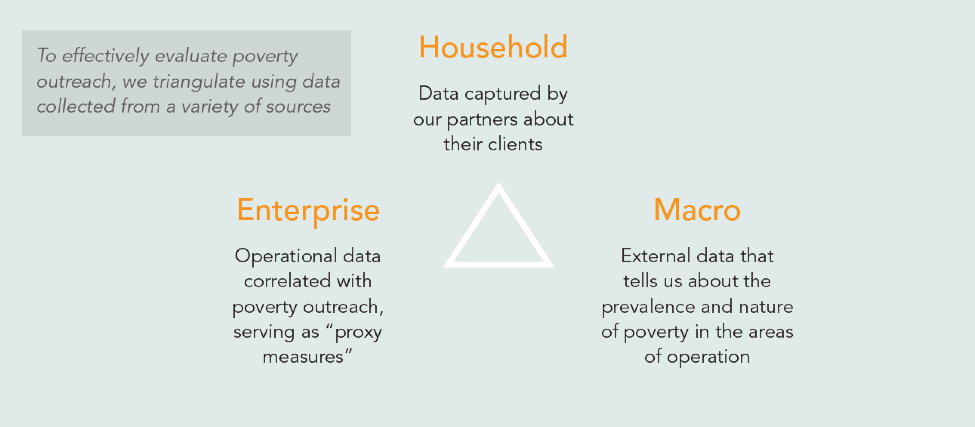

How Will We Measure It? With strategic clarity as well as measures and targets in place, we were then ready to ask how we would measure poverty in our portfolio. As a fund manager, it was critical that we develop a method that was grounded in our partners’ data and sufficiently agile for our investment process. Where we landed was a methodology that triangulates between three types of poverty data, which we refer to as macro, enterprise, and household data.

Early in our investment process and/or when other poverty data is limited, we leverage macro data to gain confidence that the partner has the capacity to reach our target market. In this analysis, we look at the national headcount ratio against the IPLs, but we also map enterprise activity against the UN’s Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), which helps us better understand not only the prevalence, but also the nature of poverty in the enterprise’s regions of operation. As due diligence progresses, we dig into enterprise proxies such as average loan size, delivery mechanism and product price to gain additional confidence that the offering is designed to reach our target market. Finally, when available we compare this data with household survey data, such as that captured by the Poverty Probability Index® (PPI®).

With roughly 30% of our social enterprise partners using the PPI, it is by far the most standardized tool used to capture household poverty data in our portfolio. That being said, usage of the tool varies widely and with many partners using dated tools and/or reporting against national poverty lines, we often need to interpret reported results against our targets (the $3.20 and $5.50 per person/day 2011 PPP lines). It is not a perfect science, but it provides the directional data needed to estimate poverty outreach within our target market. To complement this, we have integrated the PPI into targeted assessments, first through in-person client surveying with Microfinance Opportunities and now through mobile-based client surveying with Acumen’s Lean DataSM approach. Conducting these assessments not only provides us with valuable first-hand poverty data, it also helps us test and improve on the accuracy of our triangulated analysis. For example, we recently conducted Lean Data Assessments with two of our solar partners. During underwriting we relied on macro and enterprise data to gain confidence that the enterprises were reaching customers living under $3.20/person/day. Using the PPI, the Lean Data assessments validated our previous assumptions and provided increased clarity regarding the percent of customers living within our target market. This information has been valuable to not only GP, but also to the participating solar partners, who are now using the information to inform product and service design.

This point brings me to the final learning I’d like to share—and perhaps the most important. Poverty measurement has helped Global Partnerships strengthen our relationships and align expectations. Downstream, it has facilitated a deeper understanding of our partners’ poverty outreach and enabled us to engage in strategic conversations about inclusive growth. Upstream it has enabled us to find investors who share our commitment to those marginalized by depth of poverty and manage return expectations accordingly.

Tara Murphy Forde is the Senior Vice President, Research & Impact at Global Partnerships (GP). Tara leads GP’s efforts to define, measure, and strengthen the impact of its investments. In this capacity she oversees the qualitative and quantitative methods, tools, and processes used to identify high-impact opportunities and cultivate learnings from the existing portfolio. She joined GP in January 2009. Prior to her role on the Research and Impact Team, Tara spent five years on GP’s Social Investment Team where she was responsible for the monitoring and evaluation of Fund performance. Her approach to impact investing is informed by academic, professional, and entrepreneurial experience addressing the issues of poverty, gender and conflict. As a Fulbright Scholar, Tara researched the gender-differentiated effects of the armed conflict in Colombia and was part of a start-up tackling the socio-economic reintegration of displaced families. In addition to her time in Colombia, Tara has lived and studied in Cuba and Northern Ireland. Tara holds a B.A. in political science from Vassar College and a certificate in executive leadership from the Albers School of Business at Seattle University.

[1] A PPP exchange rate is the number of units of local currency required to buy the same amount of goods and services in a country as one U.S. dollar would buy in the United States.